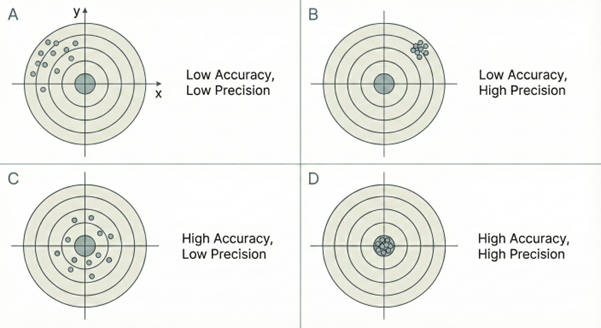

Accuracy vs Precision

Why Quiet Data Misleads AI Teams

AI teams often work with sensor data long after the measurement has passed through tubing, filters, firmware, environmental interfaces, and digital pipelines. When the signal looks calm, with tight clustering or low variability, it is easy to describe it as high precision or to assume the values are accurate enough for modelling. In sensing work, that assumption is unsafe. A signal can be quiet for reasons that have nothing to do with measurement quality: blocked flow paths, mechanical damping, quantisation, thermal settling, or smoothing applied by firmware.

Understanding the distinction between accuracy and precision is essential whenever an AI or data science workflow relies on physical measurements. The difference determines whether a team is modelling the real system or modelling an artefact created somewhere in the measurement chain.

Accuracy: agreement with the real physical quantity

Accuracy describes how closely a reported value matches the real behaviour of the system. In sensor work there are two forms of accuracy, and they must be kept separate.

True accuracy

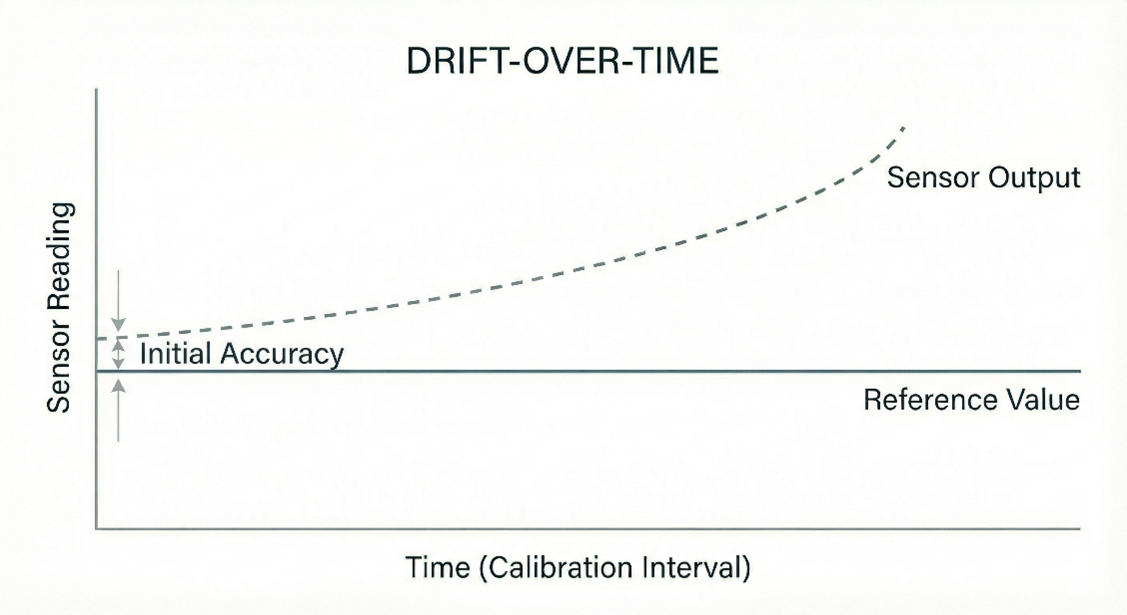

True accuracy is agreement with the actual physical quantity under real environmental conditions. It must account for how the sensor behaves across the full calibration interval in the expected operating environment. Temperature cycles, mounting stresses, drift, hysteresis, and environmental coupling all influence true accuracy over time. A sensor can begin its service life close to the real value and then shift as it experiences load, thermal changes, moisture, or gradual drift. True accuracy refers to how the measurement behaves in use, not how it behaved at the bench during calibration.

Calibration accuracy

Calibration accuracy is agreement with a calibration reference. The reference might be a high-accuracy standard such as a precision pressure transducer, voltage source, or load cell, or it might be a physically generated quantity such as a controlled pressure step or a known weight. Calibration accuracy describes the sensor at the moment it was compared with the reference in controlled conditions, and it does not account for drift or mounting effects.

Installation factors such as tubing length, line impedance, mounting stress, soil coupling, vibration, and thermal gradients can shift the real signal away from the behaviour observed during calibration. A sensor can pass calibration with excellent results but deliver poor true accuracy once installed, and that gap can widen as drift accumulates through the calibration period.

Calibration reports describe the sensor in an ideal state. True accuracy describes the sensor in the real world across time.

Precision: the repeatability of the measurement, not its correctness

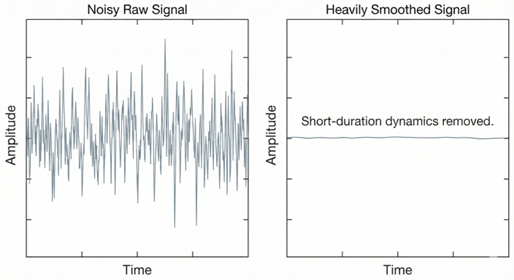

Precision describes how tightly repeated measurements cluster under fixed conditions. It reflects noise, filtering, damping, digital resolution, and environmental stability. High precision does not confirm correctness.

False precision is common in field data. A pressure transducer can show extremely stable readings because the impulse line feeding it is partially blocked. The trapped fluid column creates an artificially quiet environment, while the real pressure dynamics in the wellbore never reach the sensor. The signal appears orderly, but the measurement is wrong.

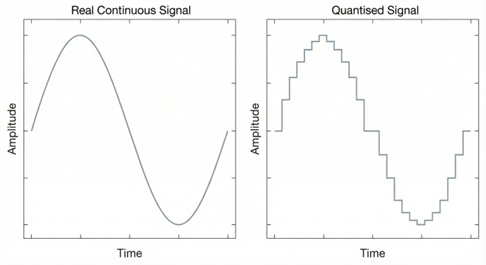

Digital rounding or quantisation can also produce false precision. Identical consecutive values may suggest stability, but they simply reflect coarse digital steps that hide genuine variation. Some firmware applies long averaging windows to hide noise. This creates a smooth signal but removes short-timescale behaviour that may be essential for understanding the physics.

When AI teams see quiet data, they often assume measurement quality. In many cases, quiet data is the first sign that the physical pathway to the sensor is compromised.

Why AI teams are misled

AI workflows are usually built around the data that reaches the modelling stage. By that point, the measurement may have been shaped by:

mechanical damping in tubing or mounting

thermal settling or gradients

sensor firmware filters

low-resolution ADCs

digital smoothing or decimation

environmental coupling through soil or structures

Each transformation alters the signal. None of these transformations are visible in notebooks or dashboards. As a result, AI teams tend to evaluate data quality by appearance, such as noise level or smoothness, rather than by physical credibility.

Calibration documentation adds further confusion. A sensor can show excellent calibration accuracy but perform poorly once installed. Without understanding the installation path and how it changes over time, a calibration certificate can give misplaced confidence.

How AI teams should evaluate signals

To avoid training models on misleading data, AI practitioners should:

Check for quantisation or rounding.

Look for repeated values, step changes, or long flat segments that do not match expected physical behaviour.

Examine dynamics.

A real system responds to changes in pressure, load, or temperature. If the signal does not move when it should, examine the measurement path or look for excessive filtering in firmware or post-processing.

Review calibration information.

Determine what the reference was. Agreement with a reference in controlled conditions does not guarantee correct behaviour in the field.

Understand the sensing pathway.

Ask how the signal reaches the sensing element. Tubing, mounting, soil, temperature, vibration, and structural coupling all influence true accuracy.

Treat quiet data as a diagnostic clue.

Calm or low-scatter signals can indicate measurement distortion, not measurement quality.

Validate both scatter and bias.

Precision (scatter) and accuracy (bias) require separate validation steps. One does not imply the other.

Expert judgement

Accuracy and precision cannot be inferred from the dataset alone because the signal entering the AI pipeline has passed through a physical system whose behaviour is rarely visible to data teams.

Closing point

AI models that rely on sensor data perform well only when the underlying measurements reflect real physical behaviour. When accuracy and precision are assumed rather than validated, models can appear strong in development and then fail immediately in the field. For any sensing-driven AI work, the first task is to confirm whether the signal represents real behaviour, repeatable behaviour, or only the artefacts of the measurement chain.